From: Zack M Davis <zmd@sfsu.edu>

Sent: Sunday, January 12, 2025 11:52 AM

To: math_majors@lists.sfsu.edu <math_majors@lists.sfsu.edu>, math_graduate@lists.sfsu.edu <math_graduate@lists.sfsu.edu>, math_lecturers@lists.sfsu.edu <math_lecturers@lists.sfsu.edu>, math_tenure@lists.sfsu.edu <math_tenure@lists.sfsu.edu>

Subject: the end of the movie: SF State’s 2024 Putnam Competition team, a retrospective

Because life is a gradual series of revelations

That occur over a period of time

It’s not some carefully crafted story

It’s a mess, and we’re all gonna dieIf you saw a movie that was like real life

You’d be like, “What the hell was that movie about?

It was really all over the place.”

Life doesn’t make narrative sense—“The End of the Movie”, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Every Hollywood underdog story starts with a dream. The scrawny working-class kid who wants to play football for Notre Dame. The charismatic teacher at a majority-Latino school in East L.A. who inspires his class to ace the AP Calculus exam. The debate team at a historically black college that unseats the reigning national champions. Hollywood tells us that if you work hard and believe in yourself, you can defy all expectations and achieve your dream.

Hollywood preys on the philosophically unsophisticated. Chebyshev’s inequality states that the probability that a random variable deviates from its mean by more than k standard deviations is no more than 1/k². Well-calibrated expectations already take into account how hard you’ll work and how much you’ll believe in yourself: underdogs mostly lose by definition.

Accordingly, this story starts with a correspondingly humble dream: the not-a-kid-anymore returning to SFSU after a long absence to finish up his math degree, who wants to get a nonzero score in the famous William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition®. (It’s not quite as humble as it sounds: the median score in the famously brutal elite competition is often zero out of 120, although last year the median was nine.)

The first step on the road to a nonzero score was being able to compete at all: SF State had no immediate history of participating in the event, in contrast to other schools that devote significant resources to it. (E.g., at Carnegie Mellon, they have a for-credit 3-unit Putnam seminar that meets six days a week.) At SFSU in 2012, I had asked one of my professors about registering for the Putnam, and nothing came of it. This time, a more proactive approach was called for. After reaching out to the chair and several professors who had reasons to decline the role (“I’m not a fan of the Putnam”, “I have negative time this semester”, “You should ask one of the smart professors”), Prof. Arek Goetz agreed to serve as local supervisor.

A preparation session #1 to discuss the solutions to problems from the 2010 competition was scheduled and aggressively advertised on the math-majors mailing list. (That is, “aggressively” in terms of the rhetoric used, not frequency of posts.) Despite some interest expressed in email, no non-organizer participants showed up, and my flailing attempts at some of the 2010 problems mostly hadn’t gotten very far … but I had at least intuited the correct answer to B2, if not the proof. (We are asked about the smallest possible side of a triangle with integer coordinates; the obvious guess is 3, from the smallest Pythagorean triple 3–4–5; then we “just” have to rule out possible side lengths of 1 and 2.) The dream wasn’t dead yet.

To keep the dream alive, recruitment efforts were stepped up. When I happened to overhear a professor in the department lounge rave about a student citing a theorem he didn’t know on a “Calculus III” homework assignment, I made sure to get the student’s name for a group email to potential competitors. A When2Meet scheduling poll sent to the group was used to determine the time of prep session #2, which was advertised on the department mailing list with a promise of free donuts (which the department generously offered to reïmburse).

Session #2 went well—four participants came, and Prof. Goetz made an appearance. I don’t think we made much progress understanding the 2011 solutions in the hour before we had to yield TH 935 to the Ph.D. application group, but that wasn’t important. We had four people. This was really happening!

As the semester wore on, the group kept in touch on our training progress by email, and ended up holding three more in-person sessions as schedules permitted (mean number of attendees: 1.67). Gelca and Andreescu’s Putnam and Beyond was a bountiful source of practice problems in addition to previous competitions.

Finally, it was Saturday 7 December. Gameday—exam day, whatever. Three competitors (including one who hadn’t been to any of the previous prep sessions), gathered in the Blakeslee room at the very top of Thornton Hall to meet our destiny. The Putnam is administered in two sessions: three hours in the morning (problems identified as A1 through A6 in roughly increasing difficulty), and three hours in the afternoon (problems B1 through B6).

Destiny was not kind in the problem selection for the “A” session.

A1 was number theory, which I don’t know (and did not, unfortunately, learn from scratch this semester just for the Putnam).

I briefly had some hope for B2, which asked for which real polynomials p is there a real polynomial q such that p(p(x)) − x = (p(x) − x)²q(x). If I expanded the equation to Σj=0n aj(Σk=0n ak xk)j − x = (Σj=0n aj xj − x)² Σj=1n bj xj, and applied the multinomial theorem … it produced a lot of impressive Σ–Π index notation, but didn’t obviously go anywhere towards solving the problem.

A3 was combinatorics. Concerning the set S of bijections T from {1, 2, 3} × {1, 2, …, 2024} to {1, 2, …, 6072} such that T(1, j) < T(2, j) < T(3, j) and T(i, j) < T(i, j+1), was there an a and c in {1, 2, 3} and b and d in {1, 2, …, 2024} such that the fraction of elements T in S for which T(a, b) < T(c, d) is at least ⅓ and at most ⅔? I couldn’t get a good grasp on the structure of S (e.g., how many elements it has), which was a blocker to being able to say something what fraction of it fulfills some property. Clearly a lexicographic sort by the first element, or by the second element, would fulfill the inequalities, but how many other bijections were in S? When the solutions were later published, the answer turned out to involve a standard formula about Young tableaus, not something I could have realistically derived from scratch during the exam.

A4 was more number theory; I didn’t even read it. (I still haven’t read it.)

A5 asked about how to place a radius-1 disc inside a circle of radius 9 in order to minimize the probability that a chord through two uniformly random points on the circle would pass through the disk. I recognized the similarity to Bertrand’s paradox and intuited that a solution would probably be at one of the extremes, putting the disc at the center or the edge. There was obviously no hope of me proving this during the exam. (It turned out to be the center.)

A6 was a six; I didn’t read it.

I turned in pages with my thoughts on A2, A3, and A5 because it felt more dignified than handing in nothing, but those pages were clearly worth zero points. The dream was dying.

Apparently I wasn’t the only one demoralized by the “A” problems; the other competitors didn’t return for the afternoon session. Also, it turned out that we had locked ourselves out of the Blakeslee room, so the afternoon session commenced with just me in TH 935, quietly hoping for a luckier selection of “B” problems, that this whole quixotic endeavor wouldn’t all have been for nothing.

Luck seemed to deliver. On a skim, B1, B2, and B4 looked potentially tractable. B2 was geometry, and I saw an angle of attack (no pun intended) …

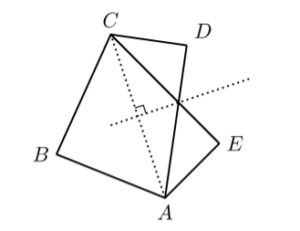

B2. Two convex quadrilaterals are called partners if they have three vertices in common and they can be labeled ABCD and ABCE so that E is the reflection of D across the perpendicular bisector of the diagonal AC. Is there an infinite sequence of convex quadrilaterals such that each quadrilateral is a partner of its successor and no two elements of the sequence are congruent?

I imagined rotating the figure such that AC was the vertical axis and its bisector was the horizontal axis, and tried to imagine some way to perturb D and E to get a sequence of quadrilaterals that wouldn’t be congruent (because the angles ∠CDA and ∠CEA were changing), but for which we could alternately take ABCD and ABCE so that successive shapes in the sequence would be partners. I couldn’t see a way to make it work. Then I thought, what if perturb B instead?

Yes, I began to write excitedly, there exists such a sequence. For example, in ℝ², let A := (0, −1), C := (0, 1), D := (½, ½), and E := (½, −½), and consider a sequence Bn on the unit circle strictly in quadrant II (i.e., with x < 0 and y > 0), for example, Bn := (Re exp((π - 1/n)i), Im exp((π - 1/n)i)) where ℝ² is identified with ℂ. Then consider the sequence of quadrilaterals ABnCD for odd n and ABnCE for even n, for n ∈ ℕ+. Successive quadrilaterals in the sequence are partners: the perpendicular bisector of the diagonal AC is the x-axis, and D = (½, ½) and E = (½, −½) are reflections of each other across the x-axis. No two quadrilaterals in the sequence are congruent because the angle ∠ABnC is different for each n …

Or is it? I recalled a fact from Paul Lockhart’s famous lament: somewhat counterintuitively, any triangle inscribed in a semicircle is a right triangle: ∠ABnC would be the same for all n. (The quadrilaterals would still be different, but I would have to cite some other difference to prove it.) I took a fresh piece of paper and rewrote the proof with a different choice of Bn: instead of picking a sequence of points on the unit circle, I chose a sequence on the line y = x + 1: say, Bn := (−1/(n+1), 1 − 1/(n+1)). Then I could calculate the distance AB as √(1/(n+1)² + (1 − 1/(n+1))²), observe that the angle ∠BCA was 45°, invoke the law of sines to infer that the ratio of the sine of ∠ABC to the distance AC (viz., 2) was equal to the ratio of the sine of ∠BCA (viz., √2/2) to the distance AB, and infer that ∠ABC is arcsin(√2/AB‾), and therefore that the quadrilaterals in my sequence were not congruent. Quod erat demonstrandum!

That took the majority of my time for the afternoon session; I spent the rest of it tinkering with small-n cases for B1 and failing to really get anywhere. But that didn’t matter. I had solved B2, hadn’t I? That had to be a solve, right?—maybe 8 points for less than immaculate rigor, but not zero or one.

Last year the published contest results only listed the names of top 250 individuals, top 10 teams, and top 3 teams by MAA section (“Golden Section: Stanford University; University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Davis”), but I fantasized about looking up who I should write to at the MAA to beg them to just publish the full team scores. Who was privacy helping? People who go to R2 universities already know that we’re stupid. Wouldn’t it be kinder to at least let us appear at the bottom of the list, rather than pretending we didn’t exist at all? All weekend, in the movie of my life in my head, I could hear the sports announcer character (perhaps portrayed by J. K. Simmons) crowing: Gators on the board! Gators on the board!

All weekend and until the embargo period ended on 10 December and people began discussing the answers online, reminding me that real life isn’t a movie.

I did not write to the MAA.

The Gators were not on the board.

I did not solve B2.

The answer is No, there is no such sequence of quadrilaterals. The Putnam archive solutions and a thread on the Art of Problem Solving forums explain how to prove it.

As for my “proof”, well, the problem statement said that partner quadrilaterals have three vertices in common. In my sequence, successive elements ABnCD and ABn+1CE have two vertices in common, A and C.

This isn’t a fixable flaw. If you have the reading comprehension to understand the problem statement, the whole approach just never made any sense to begin with. If it made sense to me while I was writing it, well—what’s that phrase mathematicians like to use? Modus tollens.

You could say that there’s always next year—but there isn’t, for me. Only students without an undergraduate degree are eligible to take the Putnam, and I’m graduating next semester. (In theory, I could delay it and come back in Fall 2025, but I’m already graduating fifteen years late, and no humble dream is worth making it fifteen and a half.)

I keep wanting to believe that this isn’t the end of the movie. Maybe this year’s effort was just the first scene. Maybe someone reading this mailing list post will hear the call to excellence and assemble a team next year that will score a point—not out of slavish devotion to Putnam competition itself, but to what it represents, that there is a skill of talking precisely about precise things that’s worth mastering—that can be mastered by someone trying to master it, which mastery can be measured by a wide-ranging test with a high ceiling and not just dutiful completion of course requirements.

Maybe then this won’t all have been for nothing.