MINUETTE: So, uh, what are you studying these days?

MOON DANCER: Science, magic, history, economics, pottery. Things like that.

MINUETTE: Yowza! You planning on being a professor or something?

MOON DANCER: No.

MINUETTE: So you're just ... studying!

MOON DANCER: Can I go now?

—My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, "Amending Fences"

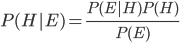

However, this corresponds to a general pattern of causal relationships: observations on a common consequence of two independent causes tend to render those causes dependent, because information about one of the causes tends to make the other more or less likely, given that the consequence has occurred. This pattern is known as selection bias or Berkson's paradox in the statistical literature (Berkson 1946) and as the explaining away effect in artificial intelligence (Kim and Pearl 1983). For example, if the admission criteria to a certain graduate school call for either high grades as an undergraduate or special musical talents, then these two attributes will be found to be correlated (negatively) in the student population of that school, even if these attributes are uncorrelated in the population at large. Indeed, students with low grades are likely to be exceptionally gifted in music, which explains their admission to the graduate school.

—Judea Pearl, Causality

"It would be nice if implementation languages provided extensible string-indexable arrays as a built in type constructor, but with the exception of awk, Perl, and a few others, they don't. There are several ways to implement such a mechanism.

—Modern Compiler Design by Dick Grune, Henri E. Bal, Ceriel J. H. Jacobs, and Koen G. Langendoen (2000)

Continue reading →